Australia’s Military History FAQs

Australia has a rich and storied military history.

Here are answers to some of the most frequently asked questions.

Wending their way home after an ANZAC Eve function in the early hours of ANZAC Day 1927, five members of the Australian Legion of Ex-Service Clubs, Messrs J. Davidson, E. Rushbrook, G. Patterson, L. Stickler, and W. Gamble observed an elderly woman laying a sheaf of flowers on the Cenotaph. One of them asked the woman if she would allow them to join her in her tribute and they all bowed their heads in silent prayer.

Caption: At the going down of the sun and in the morning we will remember them.

At a subsequent meeting of the Legion, it was decided that a Wreath Laying Ceremony would take place at the Sydney Cenotaph at 04.30 hours every ANZAC Day. This was the time that the first troops landed at ANZAC Cove in 1915.

Very little publicity was accorded that first simple ceremony. However, in 1928, about 150 people were present. The following year, an open invitation brought 250 people and prayers and bugle calls were added.

In 1930, representatives of the Federal and State Governments and more than 1,000 people attended. The State Governor of the day, Sir Phillip Game, began what was to become almost a Vice Regal duty when he attended in 1931. Another first that year was the provision of special trams, trains and buses, which greatly increased the public participation.

The Service continued to grow and in 1933 the representatives of the 3rd Brigade, the first troops to land on the shore at Gallipoli, 9th Battalion of Queensland, the 10th Battalion of South Australia, the 11th Battalion of Western Australia and the 12th Battalion of Tasmania were invited to attend and that year the attendance was more than 8,000.

By 1935, the 20th Anniversary of ANZAC was one of the biggest to that time 10,000 attending and in 1939 with the threat of another war imminent 20,000 were there.

According to what was known years ago to the New South Wales Ordnance Department, it was born from a shortage of helmets during the South African war.

Sir Harry Chauvel traced the hat from tyrolean style first worn by the South African police and later (in the early 1890’s) by the Victorian Mounted Rifle Regiment.

The first unit to top its uniform off with the slouched felt hat was the Imperial Bushmen’s Corps, which was raised by public subscriptions on a federal basis in January 1900.

Military stocks were notoriously short at this transitional period of Federation, and in Adelaide, at least, that hat was simply an emergency issue.

The Poet Laureate (John Masefield) paid the following tribute to that hat:

“Instead of an idiotic cap that provided no shade to the eye, or screen for the back of the neck, that would not stay on in a wind, no help to disguise the wearer from air observation, these men (the Diggers) wore comfortable soft felt slouch hats that protected in all weather and at all time looked well.”

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.”

The Ode comes from For the Fallen, a poem by the English poet and writer Laurence Binyon (1869 – 1943) and was published in London in The Winnowing Fan: Poems of the Great War in 1914. The verse which became the League Ode was already used in association with commemoration services in Australia in 1921.

For the Fallen

With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children

England mourns for her dead across the sea,

Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit,

Fallen in the cause of the free.

Solemn the drums thrill: Death august and royal

Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres,

There is music in the midst of desolation

And glory that shines upon our tears.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eyes, steady and aglow,

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again,

They sit no more at familiar tables of home,

They have no lot in our labour of the daytime,

They sleep beyond England’s foam.

But where our desires and hopes profound,

Felt as a well-spring that is hidden from sight,

To the innermost heart of their own land they are known

As the stars are known to the night.

As the stars shall be bright when we are dust,

Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain,

As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness,

To the end, to the end, they remain.

– Robert Laurence Binyon (1869-1943)

The red poppy, the Flanders’ poppy, was first described as the flower of remembrance by Colonel John McCrae, who was Professor of Medicine at McGill University of Canada before World War I. Colonel McCrae had served as a gunner in the Boer War, but went to France in World War I as a medical officer with the first Canadian contingent.

At the second battle of Ypres in 1915, when in charge of a small first-aid post, he wrote in pencil on a page torn from his despatch book:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place, and in the sky

The larks still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders’ fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe,

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders’ fields.

The verses were apparently sent anonymously to the English magazine ‘Punch’, which published them under the title, “In Flanders’ Fields”.

Colonel McCrae was wounded in May 1918 and died after three days in a military hospital on the French coast. On the eve of his death he allegedly said to his doctor “Tell them this. If ye break faith with us who die we shall not sleep”.

An American Miss Moira Michael, read “In Flanders’ Fields” and wrote a reply entitled “We Shall Keep the Faith”:

Oh! You who sleep in Flanders’ fields,

Sleep sweet – to rise anew,

We caught the torch you threw,

And holding high we kept

The faith with those who died,

We cherish, too, the Poppy red

That grows on fields where valor led.

It seems to signal to the skies

That blood of heroes never dies,

But lends a lustre to the red

Of the flower that blooms above the dead

In Flanders’ fields.

And now the torch and Poppy red

Wear in honour of our dead

Fear not that ye have died for naught

We’ve learned the lesson that ye taught

In Flanders’ fields.

The poppy, bloomed profusely on the battlefields of the Western Front in France during World War I. Legend has it that the poppy goes back to the time of the famous Mongol leader, Genghis Khan and is symbolic of the spirit of service and sacrifice.

The poppy was first made for an appeal in France and a group of widows of French ex-servicemen called on Earl Haig at the British Legion Headquarters and suggested they might be sold as a means of raising money to aid the distress amongst those who were incapacitated as a result of war. These first poppies were sold in the streets of London on Armistice Day 1921.

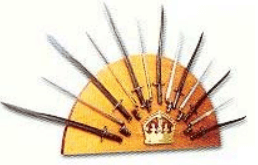

Proudly worn by soldiers of the 1st and 2nd Australian Imperial Forces in both World Wars, the ‘Rising Sun’ badge has become an integral part of Digger tradition.

The distinctive shape, worn on the upturned brim of a slouch hat, is readily identified with the spirit of ANZAC.

Yet despite the badge’s historic significance, well researched theories as to its origin are more numerous than its seven extended points.

In 1902 a badge was urgently sought for the Australian contingents raised after Federation for service in South Africa during the Boer War.

Probably the most widely accepted version of the origin of this badge is that which attributes the selection of its design to a British officer, Major General Sir Edward Hutton, KCB, KCMG, the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Forces.

He had earlier received as a gift from Brigadier General Joseph Gordon, a military acquaintance of long-standing, a “Trophy of Arms” comprising mounted cut and thrust swords and triangular Martini Henri bayonets arranged in a semi-circle around a brass crown. To Major General Hutton the shield was symbolic of the coordination of the Naval and Military Forces of the Commonwealth.

The original badge design created and produced in haste for issue to the contingent departing to South Africa was modified in 1904. This modified badge was worn through both World Wars. Since its inception the basic form of the 1904 version has remained unchanged although modifications have been made to the wording on the scroll and to the style of crown.

In 1949, when Corps and Regimental badges were reintroduced into service, the wording on the scroll of the “Rising Sun” Badge was changed to read “Australian Military Forces”.

Twenty years later, the badge was again modified to incorporate the Federation Star and Torse Wreath from the original 1902 version of the badge and the scroll wording changed to “Australia”.

In the 75th anniversary year of the ANZAC landings at Gallipoli there arose a desire to return to the traditional accoutrements worn by Australian soldiers during the World Wars, which clearly identify the Australian Army. The change coincided with the 90th anniversary of the Army, which was commemorated on 1st March 1991.

Comprehensive lists and records can be found across the following resources:

- Australia at war (Federal Government)

- Australians at war (Australian War Memorial)

- List of wars involving Australia (Wikipedia)

Rosemary is a native of the south of Europe and an evergreen shrub (Rosmarinus Officinalis), of the family ‘Labiatae’, its name meaning ‘Dew of the Sea’.

As a member of the mint family it has long been used medicinally, the oil from its crushed leaves and stems, for many disorders and a tea made from the leaves was used to quieten nerves and strengthen memory. The leaves are also used in perfumery and cooking.

As early as 1584, rosemary has been used for remembrance and an emblem for particular occasions such as funerals and weddings or as a decoration for brides dating from 1601.

Shakespeare makes reference to rosemary in Hamlet (Act IV Scene 5) where Ophelia, decked with flowers, says to Laertes: “There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance”.

For most Australians, the significance of rosemary came to Australia with the first influx of people to this continent. It is therefore reasonable to assume that a combination of old traditions and customs together with the occurrence of the landing at Gallipoli in the area where rosemary grows wild and abundantly, gives rise to the use of this little shrub as a token of remembrance in recalling the memory of the fallen and the reasons for their deaths.

The various badges of rank and insignia can be viewed on the Department of Defence website using the following links:

The purple poppy is a symbol of remembrance for animals that have served during wartime. It is often used in wreaths or as a lapel pin, primarily in the United Kingdom.

The symbol of the purple poppy was first created in 2006 by the charity Animal Aid.

Historically, horses have been the greatest animal casualties of war (approximately eight million horses and donkeys died in the First World War). However in contemporary service, military working dogs are the more commonly serving animals.